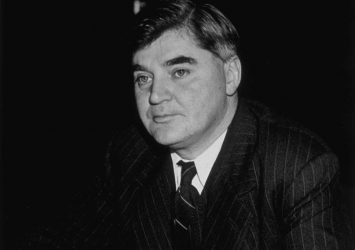

Aneurin Bevan: A Tribute

November 25th, 2018

The miner’s teenage son who walked the Welsh hills reciting poetry and recounting history, mixing longer Latin words with pithy Anglo-Saxon ones partly to help his stammer, became the father of the National Health Service. A piercing but not Left-leaning historian, surveying the first half of the 20th century, has written: “He deserves the laurel crown as the British politician who did least harm and most good.” (1)

Aneurin Bevan early showed his steel at school by fighting bullying, standing up for others – and rebelling. These qualities flowed as he moved through pit miners’ committees, his union and local council, becoming known for his determination to get things done and improve people’s lots, helped by his eloquence and style, distinctive phrase-making and wit and platform ability on the hustings. He spoke for people who lacked a voice, “Nyrin tells them, see” said one using the less usual name some old friends used. It was that regard that made my grandfather hoist my four-year-old self on his shoulders in a packed hall “so that my grandson can always say he saw Nye in the flesh”. On the local hospital committee he observed Tredegar’s Workmen’s Medical Aid Society providing medical services and aids in return for members paying three pence in the pound of their wages; almost all the town’s families subscribed. It surely formed a glint in Bevan’s eye as to what a greater scheme might be.

In 1929 he brought to Parliament his radicalism, restlessness and intellect: he read widely on philosophy and history, often quoting Shakespeare and the Romantic poets. His maiden speech was thought “like some disturbance of nature” as he attacked Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George, the latter a fellow but erstwhile great radical. The duel with Churchill was to last almost 30 years and although the great war leader was to label him a “a squalid nuisance” in World War II for his criticism of war strategies Churchill saw fully Bevan’s able bravura: indeed, a curious almost-friendship between the two might sometimes be glimpsed. With Bevan’s resignation over health service charges in 1951 Churchill reminded Bevan’s wife, the redoubtable Jennie Lee, “Do not underestimate your husband.” After the Commons’ tributes at Bevan’s death in 1960 Churchill sat on alone in the chamber for a little, remembering his most formidable Parliamentary adversary.

The Speaker of India’s Parliament in 1957 called Bevan “a man of passion and compassion”. That twin tribute may be seen as key to his achievement and complex personality. His desperation to raise people up, right wrongs as he saw them, his outspokenness in following a vision he fashioned, could also mix with anger, impatience and intemperate language that could hurt his cause as well as sustain it. His ‘difficult’ volatility was seen at times in the 1930s, albeit in righteous causes of reducing unemployment and increasing social support; and even more in the 1950s, frustrated by being out of power, the long-running clash with Labour’s younger leader Hugh Gaitskell did little to help their election chances. In part it was Bevan’s ‘democratic socialism’ vying with Gaitskell’s ‘managed capitalism’, some echoes of which sound today. In this turbulence however Bevan did not relish hero-worship and he was never quite the tribal leader the word ‘Bevanite’ implies. Before their too early deaths, Gaitskell won most of their Party battles; but now he is largely forgotten while Bevan, through the NHS, remains a household name.

In his thirst for action Bevan could tongue-lash his Labour colleagues too, even Clement Attlee, that adroit manager of big personalities. But in 1945, and now Prime Minister, Attlee saw the purpose ready within his impatient colleague: “For Health, I chose Aneurin Bevan whose abilities had up to now been displayed only in opposition, but I felt he had it in him to do good service.” Bevan himself in that election pinpointed the challenge: “We have been the dreamers, we have been the sufferers, now we are the builders.”

The Bishop of London reminded us in her 2018 sermon in St Bartholomew-the-Less Church celebrating the 70th anniversary of the NHS that it was not born without opposition. Indeed. The medical profession of the 1940s was generally very conservative, fearful of ‘nationalisation’. There were over 1300 voluntary hospitals, many in financial straits; municipal hospitals run by territorially-minded local councils varied hugely. It seemed like a fight against all comers, and often was. Bevan’s hard-working determination – and charm – began to persuade the Royal Colleges that a proper health service for all could only be financed by government on a nationalised basis. In this he was aided by such as his Permanent Secretary Sir William Douglas (who had wished to retire at once when Bevan was appointed!… but was soon saying “He’s the best Minister I ever worked for”) and Churchill’s own personal doctor Lord Moran – “Corkscrew Charlie”, so called for his negotiating skill with his fellow professionals. Honey tongues were used and heads knocked together. “This is my truth: now tell me yours” was a favourite Bevan saying. Above all, Bevan showed pragmatism. Compromises were made, private practice permitted to continue, and as Bevan playfully explained in a famous phrase, “I stuffed their mouths with gold” [well, some!]. Sometimes pulling, sometimes pushing, bringing together all the different interests and practitioners in a national service was, on Bevan’s part, “a remarkably skilful achievement” (1). Since that ‘alchemy’ of 1948, despite the glitches, gripes and grumbles, the NHS and the people who serve within it do myriad marvellous things for others every day.

Leading political opponents of Bevan such as RA Butler and Harold Macmillan knew his quality. Macmillan as PM recalled, “He was a genuine man… There was nothing fake or false about him” and he gave Bevan his highest accolade “he was an artist”. David Eccles, whose father had been a noted Barts surgeon and who fought the doctors’ corner in the 1947/48 health debates, told me one night that Bevan was far and away the finest debater he saw in his 50 years in Parliament.

For his oratory could be extraordinary. It was not rhetoric but a capacity to develop arguments on his feet. Bevan’s speeches’ power lay in their “subtle, elegant but sinewy thrust… they combined irresistible logic with creative imagination… unlike most orators he could sometimes persuade opponents to change their minds” wrote Paul Johnson (2), a conservative historian who nonetheless never lost gladness that when young he had “sat under the wand of the magician” in William Pitt’s 1783 phrase of his great rival.

Sister Agnes of St Teresa’s hospital in Wimbledon told Bevan, “Minister, you are the most hated man in Britain – and the most loved.” That experience of duality, together with the vein of romance and the skill of oratory and debate, drew the comparisons in Bevan’s lifetime and since with the great 18th century figure of Charles James Fox (the original magician and his wand). Perhaps, however, Bevan might have valued most a more living tribute. The son of a young doctor’s brother was born with parlous health but treated successfully by the NHS in one of its countless accomplishments. The baby boy was then named ‘Aneurin’ after the man whose compassionate drive ushered the NHS into being and who was “that very, very rare thing in the history of politics, a man whose decisions on behalf of those he served brought about human betterment” (1).

(1) AN Wilson. After the Victorians [1901-1953]. 2005.

(2) Paul Johnson. My hero… Aneurin Bevan. The Independent Magazine, 1989.